In 2007 I had the good fortune to attend a class organized by UC Riverside at the historic Maloof residence and shop in Alta Loma. Sam Maloof was with the group almost the whole day, ending with an informal chat in his living room. The experience was inspiring and entertaining beyond words. His charm and charisma were immediately obvious. At the end of the tour he signed a copy of his autobiography for me. (Sam Maloof Woodworker by Jonathan Fairbanks 1983). I happened to open the book recently and was reminded of his huge influence on the craft of woodworking and superb qualities as a person, I thought our SDFWA members might be interested in learning more about his life.

Sam (in accord with Sam Maloof's famous modesty and humility I will refer to him by his first name) was the seventh of nine children born in Chino California in 1916 to Slimen and Anisse Maloof who emigrated from Lebanon to California by way of Ellis Island in 1905. His father sold vegetables and dry goods, his mother sold lace, embroidery and crochet work; first from a horse drawn carriage, later from a store.

He learned Arabic from his parents and Spanish from their housekeeper before he learned English. His widowed sister and her six children came to live with the family during the depression; 14 people living in the 3 bedroom house at one point. As a child Sam displayed great talent for drawing and ingenuity, fixing and making items for the home; a spatula for turning bread, carved dollhouse furniture, cars and a toy revolver with a spinning chamber. He won a Southern California high school contest to make an advertising poster for the Padua Players theater group. Sam's formal education ended after high school. He earned money painting store windows and signs on buildings. In 1940 this work led to a job as a draftsman for Harold Graham, an industrial designer.

In 1941 Sam was drafted into the Army as a private. His skills were quickly recognized and he was put to work as a draftsman. He was eventually promoted to master sergeant and later posted to the Aleutians and Alaska. After being released from active duty in 1945 he worked briefly as a graphic artist for Angelus Pacific, a decal company in Los Angeles. He enrolled in night classes at the Frank Wiggins Trade School, where he learned to use woodworking machines and started making furniture for his small apartment.

Harold Graham told Millard Sheets, a noted California artist and art director at Scripps college, about Sam in 1946. Millard Sheets hired him to do a silk screen. Over the next two years Sam worked as his assistant. Sheets introduced him to the world of painting, sculpture and other fine arts.

In 1948 Sam met Alfreda Ward who was studying for a Master of Fine Arts degree at Claremont College. They married soon after. When he could no longer give Sheets the undivided attention that studio work demanded, Sam began woodworking full time, at first, simple furniture using plywood salvaged by a friend from construction forms. To clean the plywood Sam had a tombstone cutter sandblast it which produced an attractive etched grain effect, a process later copied by U.S. Plywood. He purchased a home in a seven acre lemon grove in Ontario, California, built a workshop outfitted with rudimentary tools in the garage and began making furniture for his home.

Millard Sheets' brother-in-law photographed the interior of Sam's home for Better Homes and Gardens. The magazine then asked him to do drawings for woodworking plans to sell. He received a check for $150 for his work. He said it “seemed like $150,000”. After two years with Sheets he left his job and became a full time woodworker.

Sam's first commission was a disaster when the interior designer insisted he finish a dining table, chairs and buffet with a dreary brown stain. The client liked it all except for the color. After carting it all back to the shop and stripping the stain, the cost of materials consumed his entire commission; a mistake that he did not make again.

In 1951 Sam received a call from Henry Dreyfuss, designer of the Super G Constellation airliner, Hoover vacuum cleaners and other iconic products, who had seen and liked his furniture. Sam made a dining room table and chairs, bedroom furniture and pieces for the Dreyfuss children for a fee of $1,200. For the next five years commissions came from a designer showroom. After Individual commissions grew he took commissions directly from clients.

In 1957 a U.S. State Department sponsored program asked Sam to to go to Iran and Lebanon to provide design and technical advice to local craftsmen In Teheran he made full scale drawings for 52 pieces of furniture using plastic and metal tubing as there was no suitable wood locally. A small shop made about 60 pieces. After three months there he flew to Beirut, and selected a modern furniture factory that had kiln dried wood plus finishing and upholstery departments. He made 35 drawings for six prototypes which were built in walnut. These continued to be produced for years until the Lebanese civil war destroyed the factory. In 1963 he spent three months doing similar work in El Salvador.

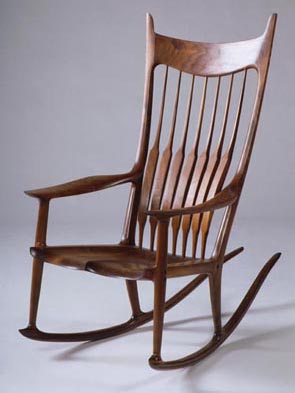

After his six month experience abroad Sam returned to California and quickly became recognized as a master of design and workmanship. In 1957 the American Craft Museum in New York presented his work in its first ever exhibition of a studio craftsman. He soon had a large backlog of commissions. Permanent collections of his furniture are now held in the, Metropolitan, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Renwick and Boston Museums of art. Several U.S. presidents placed his renowned rocking chairs in the White House.

Over the next five decades, with the help of long time assistants (usually three) and an apprentice, Sam's output steadily increased from 50 to 300 pieces of furniture annually, to a point where clients were willing to wait years for delivery; cradles for an expected baby were moved to the head of the line. Sam's test for a new apprentice was to have the apprentice sand a part which Sam had shaped. If sanding destroyed the part, the apprentice failed the test.

In 1985 Sam Maloof became the first craftsman to receive a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship. The distinctive Maloof style is difficult to characterize, with elements of Scandinavian and Shaker design blended with subtle, organic curves, highly original joinery and wonderful surfaces. He was not a purist about joinery and used screws where pieces were too thin for a dowel or mortise and tenon. One only has to look at one of his drawings to appreciate his skill as a draftsman (see the last link below).

Sam used his own body to develop comfortable chair measurements and proportions. He loved hand tools but had no reservations about using machines. His technique for shaping curved pieces included free hand cutting on a band saw (this must be seen to be appreciated) and extensive use of rasps and grinders. He invented his own finish and turned it into a commercial product, but shared the recipe with his fans; equal parts of semi gloss urethane varnish, raw tung oil and boiled linseed oil. A second version consists of equal parts of raw tung oil and boiled linseed oil plus a “by feel” amount of shredded beeswax. In different places in the book Sam states that he used a minimum of 3 or 6 applications.

He favored black walnut for most of his work; less often rosewood, English brown oak or cherry. He eventually accumulated a collection of half a million board feet of high quality lumber stored in two buildings on his property. His most complex project extended over 40 years; enlarging his home by 16 more rooms, adding handmade doors and windows, carved latches, hinges and door handles, a spiral staircase and toilet seats in English oak and walnut.

Alfreda, with whom he had a son, who also became a woodworker, and a daughter, died in 1998. Three years later Sam married Beverly Wingate, a longstanding family friend. In later years his production fell to 60 pieces annually.

In 2000 a route for the 210 Freeway project was to pass through Sam's property, threatening demolition of his home. Several of his patrons came together to have the home listed on the National Register of Historic Places. State authorities then provided funds to move the house and shop to a new site in Alta Loma, three miles away. The site, operated by The Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation for Arts and Crafts, is open for docent led tours. It includes the historic home, Sam's workshop, the Water Wise Discovery Gardens and changing exhibits at the Jacobs Education Center Gallery. Sam continued to build furniture there until a few months before his death in 2009 at the age of 93.

Links to online sources:

Sam and Alfreda Maloof Foundation

http://sammaloofwoodworker.com/

https://collections.lacma.org/search/site/maloof?f[0]=bm_field_has_image%3Atrue

https://americanart.si.edu/artist/sam-maloof-6166

https://gallery.collectorsystems.com/MaloofOnlineGallery/2354

By Dick Ugoretz (originally published on August 2018)

Editor's Note: Light edits have been made to remove broken web links.